Isra Fakhruddin

THE MAKING OF PUBLIC MEMORY

Overview | A Community “Forgotten”

In October 2019, New York City announced it would be gaining a privately-funded monument commemorating Seneca Village, a thriving community of Black entrepreneurs, property owners and families that stretched between West 83rd to 89th Street for nearly three decades before being displaced to make room for Central Park. The commissioned monument would be of Albro Lyons, Mary Joseph Lyons and their daughter Maritcha Lyons, celebrated Black abolitionists, educators, and landowners. While the representation of the Lyons family is a positive step towards discovering the history and cultures hidden within Central Park’s landscape, the monument itself is not planned to be situated anywhere near the location of the actual site. Rather, it is set to be placed 20 blocks north on 106th.

We have seen these types of initiatives before, where campaigns to honor the memory of a community or event is granted a reused idea: a stoic monument that presents itself at face value with zero room for critical analysis, interpretation, or emotional reckoning. Combined with the city’s bid to locate the Lyons’ monument outside of Seneca Village’s location, the initiative suggests a commemoration that is lacking in its attempt to tell a complete story. Not only does the plan disengage the public from recognizing the history of the community, it further displaces the memory of Seneca Village from the land of which the community worked and lived on.

Goals | Short- and Long-Term

To fully preserve the memory of Seneca Village, we must first confront the deeply embedded threads of systemic racism within the realms of planning, landscape design, architecture, and urban development. By transforming our design narrative and creating a dominant platform for Black voices, we can begin to repair and heal generations of anti-BIPOC practices that exist within our built environment.

This practice could assist in:

Preserving the narrative of Seneca Village by offering solutions to address what caused its erasure in the first place

Eminent domain, redlining, discriminatory housing practices, gentrification, etc.

Presenting a restructure of our design practice through in-depth discussion

Dismantling stigmas associated with BIPOC communities within academia and the built environment

Rethinking our Design Pedagogy

When designers seek to implement justice and storytelling through monumentation, it is imperative to recognize the way in which the stories would be perceived by the public. It is also critical to analyze the timescale in these plans.

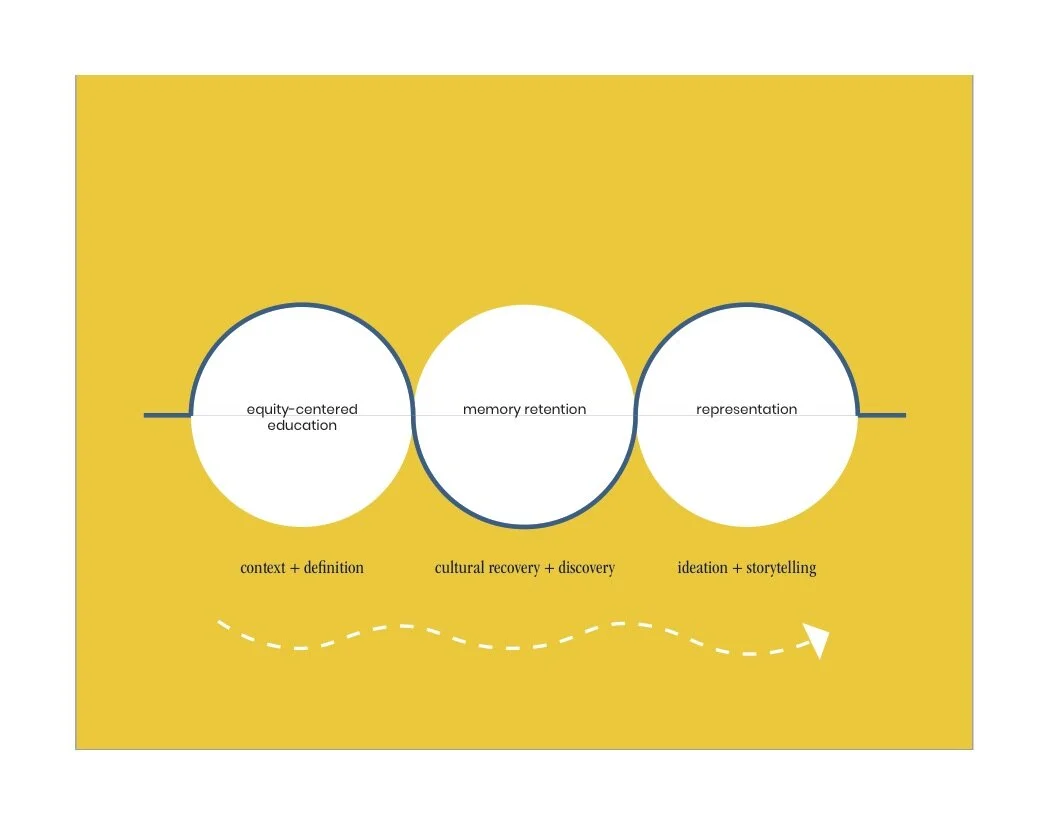

To effectively inform these stories, I believe our thought process should include a step-by-step strategy in which A) our pedagogical principles and design strategies are reformed to educate designers on how to mitigate the causes of inequity, B) study and retain the hidden stories that have shaped our built environment, and C) represent them through a critical, yet thoughtful lens.

A. Equity-Centered Education | Context & Definition

We must first initiate dialogue that allows critical thought and analysis of our built environment. By fostering an educational space in which tools are used to establish context of our society’s past injustices, designers could then feel a sense of encouragement that would help them identify, develop, and incorporate anti-racist concepts into their own design process. When anti-racist concepts are effectively integrated, it can help create a larger net of interdisciplinary processes to help define real-world systemic injustices.

Redesigning learning environments for individuals in industry and academia to explore issues of race and design, in both visible and invisible aesthetics, can also help foster a renewed path towards restorative justice within our societal framework. Some steps can include:

Unlearning colonial discourse and requiring curriculums to analyze systemic racism in design

Acknowledging that opportunities within our society are both racialized and spatialized

“The lived experience of race has a spatial dimension, and the lived experience of space has a racial dimension.”*

*The Racialization of Space and the Spatialization of Race: Theorizing the Hidden Architecture of Landscape by George Lipsitz

B. Memory Retention | Cultural Recovery & Discovery

Seneca Village currently faces a dilemma in which its story and memory is hardly in existence. By confronting an event that carries the weight of discrimination, displacement and erasure, designers can help recover the community’s cultural roots by reconciling its memory. Designers should also incite action that would reclaim the community’s original site and honor its story in its native landscape between West 83rd to 89th Street. By remembering Seneca Village within its original boundaries, its story would restructure our interpretation of Central Park’s history and allow discovery of meaningful solutions to mitigate future acts of displacement and discriminatory practice.

Other approaches to consider:

A continuous exercise of ‘rendering the void’ through system or experience

How to make the invisible, visible

Innovative techniques to provide healing opportunities for descendants of Seneca Village, as well as communities who have faced similar forms of displacement and erasure

C. Representation | Ideation + Storytelling

The final step would encourage designers to discover commemorative methods outside of the traditional, monument-based approach. Through reformed practices of equity-centered education, to reconciling Seneca Village’s memory with its original landscape, designers could then offer unique and pioneering solutions to revere the community through profound representation. We can discover new ways to ideate Seneca Village’s depiction by acknowledging the reasons for its displacement, offering strategic solutions to retain that awareness, and then enforce a commemorative model that allows viewers to not only reflect upon the past, but reflect on their own interpretations of the past. This would then help guide their engagement of reformative justice through rehabilitative and impactful storytelling.

By forgoing suggestions of stoic monuments, we can fully honor Seneca Village through poignant, dynamic design; one that incites rigor, emotion, and inspiration, and one where we can finally experience commemorative design through the lens of equity-centered reform and cultural preservation.